Drawing on his own experience from Birmingham to Liverpool, David Rudlin explores how attitudes to water and place have shaped modern urban regeneration

A few weeks ago, I was asked by the Canals and Rivers Trust to be the speaker at their Labour Party conference reception. It was a great event on a boat named Floating Grace in Salthouse Dock, with seagulls feasting on the mussels growing on the dock walls, so clean was the water.

My brief was to enthuse the delegates and others who attended about the value of canals. As they pointed out in my briefing, canals run through (or adjacent to) five of the new town sites that had been announced a few days before.

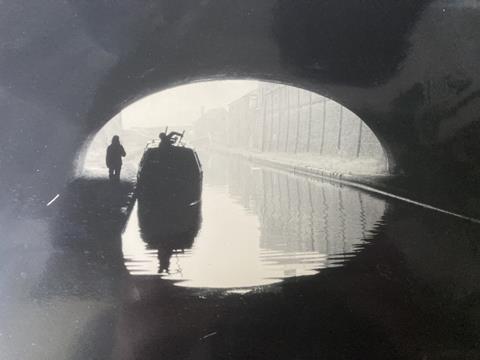

My first real experience of the canal system came when I was set a photography project by my school art teacher. It was a misty day, and my dad suggested he take me to Gas Street Basin in Birmingham.

This was the 1970s, long before its regeneration or its romanticisation (if that’s the right word) by Peaky Blinders. It was a strange half-light world of dripping moss, black brick and graffiti beneath the streets of Birmingham, and I took some great photos.

This was long before the development world understood the value of a good waterfront. My first job in Manchester, ten years later, was in the Special Projects team, responsible, amongst other things, for the city’s canals.

At that time, parts of the Rochdale Canal had been shallowed by filling it with concrete, the idea being that it still looked like a canal, but you couldn’t drown in it. It was an idea that hadn’t really been thought through because it meant that every shopping trolley and traffic cone dropped in the canal was visible.

Fast forward forty years, and I spent much of last year working on a strategy for Liverpool Waterfront, where the water in the docks is owned by the Canals and Rivers Trust. There was a time in the 1970s when Liverpool’s docks were equally unappreciated.

Queens Dock and Brunswick Dock were backfilled, and there were even proposals to turn the Royal Albert Dock basin into an underground car park as part of a huge development scheme called the Aquarius City scheme. But fortunately, attitudes changed, and it was made a conservation area, and by the 1980s regeneration was underway. Indeed, Liverpool’s remarkable renaissance as a city started on its waterfront.

This transformation in attitudes to the urban waterfront can, in part, be traced back to my colleague Nicholas Falk, who set up the Urban Waterfront project in the 1980s. He drew heavily on schemes in the US, like Quincy Market on Boston’s waterfront and Baltimore Harbour.

He also worked on the early ideas for London Docklands. One of his key statistics, drawn from the US, was that a view over water increased property values by 20%.

This magic number allowed offices and apartments to be built on industrial wastelands at a time when cities were otherwise in steep decline. It is one of those ideas that is now so obvious that it is hard to see, but at the time cities like Liverpool were entirely cut off from their water behind high dock walls, and the crumbling dock infrastructure was seen as a huge problem rather than an opportunity.

The great thing about the UK is that our urban waterfront is not confined to the coast. From the waters of Salthouse Dock, where the reception was taking place, we could have sailed (driven?) our canal boat along to the Stanley Dock via the Three Graces.

From there, a flight of locks would take us onto the Leeds–Liverpool Canal, and then via canals and navigable rivers to pretty much every significant town and city in the UK.. Our canals mean that everywhere has a waterfront and can use it as a spur to regeneration.

Pretty much all of the major projects I have worked on over my career – Temple Quay North in Bristol, Icknield Port Loop in Birmingham, Brentford Lock West and Southall Gas Works in London, Trent Basin in Nottingham – have all been next to water and have involved the regeneration of run-down industrial space as housing and mixed-use development.

And (referring to my briefing notes from the Trust) it is not just economic development and growth. There are nine million people living within a ten-minute walk of a canal, and they are brilliant resources for health and wellbeing, as havens of nature and biodiversity, as fantastic heritage assets and modern fibre-optic corridors. Not bad for a national asset that was effectively obsolete in the 1840s with the arrival of the railways.

>> Also read: Bob Allies: We’ve made Stratford Waterfront better

>> Also read: RSHP signs off on 15-year Sydney masterplan

Postscript

David Rudlin is founding principal of Rudlin & Co and visiting professor at Manchester School of Architecture.

He is a co-author of High Street: How our town centres can bounce back from the retail crisis, published by RIBA Publishing.

1 Readers' comment